A fear of dogs, known clinically as cynophobia, can significantly impact a child’s daily life. For many families, it goes beyond a mild dislike or temporary anxiety. Children who are afraid of dogs may panic during walks, dashing into the road to avoid a passing dog, or they may decline social events, such as a playdate, for fear of a dog being present in a friend’s home. This fear, often underestimated, can be both deeply rooted and emotionally overwhelming.

Parents frequently ask me, “Why is my child so scared of dogs?” The answer, like many aspects of childhood psychology, is multifaceted. And, if left untreated, the fear of dogs can start to generalise towards other animals. Many of the children I have supported not only fear dogs, but also cats, rabbits and other small animals.

Why are some children afraid of dogs?

Over the years, I have seen how the fear of dogs, or cynophobia, often disrupts family life, school trips, walks in the park, and even visits to grandparents – any setting where dogs might be present. While some children might be startled by a dog’s bark or their sudden movement, others appear predisposed to develop a far stronger, more persistent response. Data suggests specific phobias affect around 7 to 9 percent of the population, with the onset of such fears often beginning in childhood (Stangor and Walinga, 2019). Cynophobia ranks among the most common.

Contributory factors to the fear of dogs

1. Temperament and sensitivity

Some of the most compelling insights into the origins of this fear come from developmental psychology and behavioural genetics, where temperament has long been recognised as a key risk factor.

Children who are naturally more cautious or emotionally sensitive, traits often seen from infancy, tend to have a heightened vigilance toward potential threats in their environment. These temperamental traits are partly heritable, suggesting a biological component to how some children process fear. Hence, this innate sensitivity can increase the likelihood of developing future anxiety-related conditions (see point 5 for more).

Genetic research on canine behaviour offers an interesting parallel. Tiira and Lohi (2015) found that fear responses in dogs, such as anxiety towards loud noises or unfamiliar people, are heritable. This suggests that similar patterns of anxiety may run in human families too. In that case, that emotional wiring can increase the risk of forming specific fears, especially if the environment reinforces the anxiety.

2. Early childhood health and developmental experiences

Therefore, if a child is already predisposed to be more sensitive or vigilant, and early environmental experiences further shape their sensitivity, the result can be a child who is highly attuned to threats, whether those threats are real or perceived.

For example, complications in early infancy, such as premature birth, low birth weight, illness or extended hospitalisation, can influence how a child responds to perceived threats. Annapoorna (2020) found that these early adversities may reduce the threshold for fear learning later in life, potentially priming the child’s brain to overreact to uncertain or unpredictable situations. This does not mean that such children are destined to fear dogs, but they may be less resilient to the brief but intense experiences that can lay the foundation for specific phobias.

Whether a child develops a fear of dogs often hinges on the nature of their early experiences. Calm, predictable, and positive interactions tend to cultivate familiarity and confidence. However, where exposure is abrupt, chaotic, or overwhelming, the effect can be the opposite, seeding anxiety that may later bloom into full-blown cynophobia.

In my work, I have seen countless examples of this. For instance, some children I support have had their fear intensified not during direct confrontations with aggression, but simply through exposure to unfiltered canine energy. Picture a weekend visit to an aunt or grandparent’s house, where one or more excitable dogs greet the child with enthusiastic barking, leaping or zooming around the room. For a sensitive child, especially one without a steady framework of calm exposure, these moments become deeply distressing. The dog may be playing, but the child experiences this as chaos, noise, invasion of space, and crucially, a loss of control.

3. Words matter

What often compounds this fear is not the dog’s behaviour itself, but the adult response to the child’s reaction. Too frequently, we hear the same refrains: “Don’t be silly,” or “He won’t hurt you,” or “Come on, just stroke him, it’ll help.” While well-meaning, these phrases unwittingly do more harm than good.

This is where understanding how the unconscious mind processes language becomes vital.

As Bill McFarlan (2004) highlights in Drop the Pink Elephant, the brain, particularly the unconscious, emotional brain, does not register negatives in the way we assume. When someone says, “Don’t think of a pink elephant,” the first image that invariably flashes into the mind is a pink elephant. Why? Because, to interpret the instruction, the brain must first construct the image before attempting to negate it. The same mechanism is at play when a child is told, “Don’t be afraid.” The image conjured is of being afraid. “He won’t hurt you” becomes “hurt you.”

Telling a child who is visibly distressed to “just stroke the dog” as a way to overcome their fear does not address their internal state; it often overrides it. The child receives a message that their fear is invalid or irrational, which not only creates confusion but may lead to shame. The limbic system, which governs emotional memory and fear response, encodes this moment not as a safe success, but as a threat.

Moreover, insisting that a child override their bodily fear cues, without understanding, preparation, or consent, can erode trust. It teaches the child to doubt their own instincts, which is deeply counterproductive when the goal is to rebuild confidence and agency. A large-scale review by Giraudet and colleagues (2022) examined the effects of dog-child interactions and found that structured exposure during critical developmental windows supports empathy and emotional regulation. Without this, or if early encounters were frightening or overwhelming, the child may learn to associate dogs with anxiety or loss of control.

4. Parental modelling

Children learn not only from what they experience but from what they observe. Observational learning, the process by which children internalise the behaviours and emotional cues of those around them, can play a powerful role. If a parent or sibling is anxious around dogs or frequently issues cautionary warnings such as “be careful” or “stay away,” the child may learn that dogs are inherently unsafe. These associations, once established, are rarely challenged unless the child is later given safe opportunities to experience dogs in a new context. Research into social modelling supports this, showing that children are particularly susceptible to acquiring fears when they see them expressed by trusted adults (Malavanti, 2020).

5. Stress, trauma and personality

Some children may have experienced a significant negative event, such as an overly enthusiastic dog that jumped up and knocked the child over, or a dog that growled, snapped, or bit the child. If an encounter felt threatening, even if no harm was done, most children move on from such incidents, yet others do not. The reason, again, lies partly in the child’s internal makeup. Some children encode such experiences more deeply, their brains forming strong threat memories that are then generalised to all dogs. This process is well-documented in trauma studies, where emotionally charged events are more likely to create persistent behavioural patterns if not followed by corrective experiences (Cronin et al., 2020).

Even in the absence of a single traumatic moment, some children interpret everyday experiences in ways that heighten fear. Personality traits, such as introversion, perfectionism, or high imagination, can strengthen the perception of danger. These children may be more inclined to engage in catastrophic thinking, anticipating worst-case outcomes. For them, a barking dog that may be vocalising because their owner has picked up a favourite ball is not simply expressing anticipatory excitement at chasing the ball; it’s perceived as if that dog is on the verge of attack. Storengen (2017) explored these kinds of personality-linked anxiety patterns and found that such cognitive tendencies can sustain fears long after the initial trigger has passed.

Helping a child overcome their fear of dogs

And yet, what makes childhood phobias so responsive to intervention is precisely what makes them prone to formation: the plasticity of the young brain. Fears that are learned can also be unlearned, especially when approached with structure, empathy and evidence-based methods. Cognitive behavioural techniques, when combined with graded exposure and parental or guardian involvement, can reshape a child’s perception of dogs, not by forcing contact, but by building confidence through controlled, manageable steps.

This is at the heart of the Kids Around Dogs (KAD) programme. Developed as a 10-week course, it guides children and their loved ones through a gentle, structured process to reframe their understanding of dogs and rebuild confidence. The programme involves both online and face-to-face sessions, offering emotional preparation alongside practical experience. Crucially, it is about equipping the child with knowledge, agency, and safety so that they can approach dogs with calmness rather than fear. The programme provides coping strategies that last.

For many families, the transformation is huge. A child once gripped by anxiety has learnt to walk past a dog without panic and may grow to stroke, play with, and even enjoy the dog’s company – for example, two of my graduates went on to acquire a dog! More importantly, these children often develop a broader sense of emotional confidence that extends to other areas of life, from managing school-related stress to navigating new social experiences.

Fear of dogs may begin as a slight worry, but left unaddressed, it can shape a child’s relationship with the world in lasting ways. With professional, informed support, that trajectory can shift, opening the door to a far more empowered and enriching childhood that positively impacts the whole family.

If your child is struggling with fear around dogs, or if you know a family who is affected, help is available. For more information or to enquire about my availability, visit www.hannegrice.com/kids-around-dogs.

References

- Annapoorna, H. (2020) Assessing the Effectiveness of Repertory Based Individualised Homoeopathic Medicine in the Treatment of Social and Emotional Behavioral Problems in Adolescents. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/openview/68b1df25fdb4f4c286b56398d36824d7

- Cronin, D., Lazzara, J. and Rowe-Johnson, M. (2020) Psychological Disorders. In: Psychology 2e. Drake University Pressbooks. Available at: https://pressbooks.drake.edu/intropsych/chapter/psychological-disorders/

- Giraudet, C.S.E., Liu, K., McElligott, A.G. and Cobb, M. (2022) ‘Are children and dogs best friends? A scoping review to explore the positive and negative effects of child-dog interactions’, PeerJ, 10, p. e14532. Available at: https://peerj.com/articles/14532/

- Malavanti, K. (2020) Chapter 11: Psychological Disorders. In: Psychological Science: Understanding Human Behavior. Baylor Open Textbooks. Available at: https://openbooks.library.baylor.edu/psychteam/chapter/disorders/

- McFarlan, B. (2004) Drop the Pink Elephant: 15 Ways to Say What You Mean… and Mean What You Say. London: Prentice Hall Business.

- Stangor, C. and Walinga, J. (2019) Introduction to Psychology. University of Saskatchewan. Available at: https://openpress.usask.ca/introductiontopsychology/chapter/anxiety-and-dissociative-disorders-fearing-the-world-around-us/

- Storengen, L.M. (2017) Genetic Studies of Canine Anxiety. Master’s thesis. Norwegian University of Life Sciences. Available at: https://nmbu.brage.unit.no/nmbu-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2447789/2016-51_Linn%20Mari%20Storengen_(BasAm).pdf

- Tiira, K. and Lohi, H. (2015) ‘Early life experiences and exercise associate with canine anxieties’, PLoS ONE, 10(11), e0141907. Available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0141907

Learn more about our classes

Get Hanne's book, clothing and more

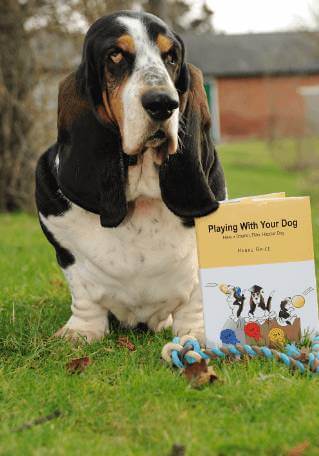

Hanne has a number of publications including her book Playing With Your Dog to help owners work out the games that are best suited for their pet to play throughout his life, from puppyhood to old age, available from Amazon. Check out Hanne's range of contemporary casuals The Collection – for pet lovers made from recyclable, organic materials that are sustainably sourced.