The New Year often feels like a natural point to take stock. For many dog owners and guardians, that means revisiting training goals and, more specifically, the behaviours that have become a source of ongoing frustration. For example, a recall that works reliably in the garden yet falls apart in the park, or a sit that looks solid at home but becomes unreliable once visitors arrive. Often this is interpreted as the dog being ‘naughty’, ‘stubborn’, or training that has somehow been lost. In most cases, what these situations highlight is not a lack of training but a misunderstanding of how learning transfers from one context to another.

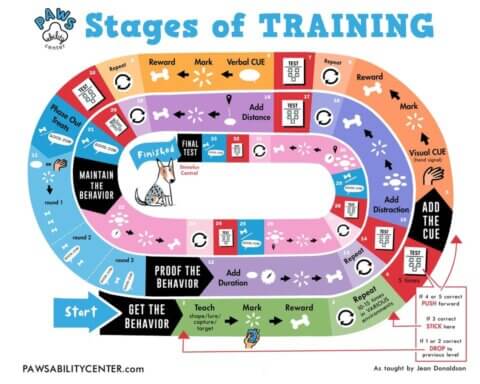

Training does not move in a straight line from ‘taught’ to ‘done’. Behaviour is learned under specific conditions, maintained by consequences, and tested every time the environment changes. The Stages of Training diagram below, published several years ago, is one that I often show clients because, rather than presenting training as a checklist to complete, it shows learning as a cycle that needs revisiting as demands increase.

What this diagram shows

Dogs do not learn behaviours in isolation; they learn relationships between actions and outcomes, cues and consequences, environments and expectations. Each stage of training serves a distinct purpose. When stages are rushed, blurred together, or skipped entirely, weaknesses tend to surface later, usually when the dog is asked to cope with greater complexity.

This becomes particularly apparent when context changes. For example, a recall trained in a low-distraction garden is being asked to function in an open space, like the local park on a busy Saturday morning, filled with scent, movement, distance, and competing motivations. Without systematic preparation, the recall behaviour remains tied to its original training conditions – the quiet garden. So, these outcomes reflect well-established learning processes, particularly the effects of context and incomplete generalisation (Braem and Mills, 2010; Gergely et al., 2014).

The diagram breaks this process into five functional stages.

1. Getting the behaviour

This is the acquisition phase. The dog learns what to do through shaping, capturing, or luring. At this point, there is no cue such as ‘Come’ or ‘Sit’. Instead, each correct response, such as the dog approaching you, or sitting their bottom to the floor, is marked (e.g., ‘yes’ or a click of a clicker) and reinforced (via food, praise, touch, play, etc.), allowing a clear contingency to form.

Learning research consistently shows that behaviour develops most reliably when consequences are predictable and contingent on the animal’s actions (Bouton, 2007). Introducing cues before the behaviour is fluent often weakens this contingency, producing behaviours that appear learned but remain vulnerable to disruption.

2. Adding the cue

A cue, such as verbal ‘Sit’ or a hand signal, becomes meaningful only once the behaviour itself is reliable. In learning terms, it functions as a discriminative stimulus, signalling that a particular response will produce reinforcement (Domjan, 2015).

When cues are introduced too early, dogs often learn associations with context rather than behaviour. The cue becomes linked to body position, routine, or location. This is why behaviours can look dependable at home and unravel elsewhere. The issue is not motivation or attitude, but incomplete stimulus control.

3. Proofing and generalisation

This is the stage where many training plans begin to unravel. The diagram separates duration, distance, and distraction because each variable increases task difficulty. When these are combined too quickly, cognitive load and arousal rise, which can disrupt learning and performance (Mills et al., 2014). From the dog’s perspective, the task has changed, even if the cue has not.

This is also where generalisation becomes critical. Dogs do not automatically transfer learning across contexts. Without deliberate exposure to new environments and competing stimuli, behaviours remain tied to their original training conditions. Experimental work has shown that dogs vary in how well they generalise trained cues, with performance shifting as task demands and environments change (Gergely et al., 2014).

This is an area I have written about extensively because it underpins many of the ‘it works at home’ cases I see. When behaviour unravels outdoors, it almost always reflects a generalisation gap rather than a lack of effort. You can read more about how this process works here.

4. Testing and maintenance

Testing appears repeatedly in the diagram because it provides information about the training plan. When a behaviour fails under test conditions, it indicates that the current reinforcement history does not yet support performance at that level of difficulty. In other words, owners may unwittingly be fading out rewards via food/fun too quickly when the behaviour is not well established across contexts.

Maintenance keeps behaviour functional through appropriate reinforcement schedules. Behavioural research demonstrates that gradual, thoughtful thinning of reinforcement supports long-term reliability far better than removing reinforcement abruptly.

5. Stimulus control and clarity

At the centre of the diagram sits stimulus control. The cue predicts the behaviour (e.g., a verbal ‘Fido – come’), and the behaviour itself (coming to the owner and staying with them) predicts a consequence (e.g., praise, touch, play, food, moving along, etc.). The response is no longer dependent on visible food, familiar routines, or specific locations.

This level of clarity takes time and systematic exposure. Attempts to shortcut this stage tend to produce behaviours that appear reliable until the context shifts. This is why owners should be very wary of ‘quick fix’ solutions, as these almost always lead to fallout and other issues.

So why does behaviour seem to go backwards?

What owners often describe as regression is better understood as behaviour encountering conditions outside its learning history. The responses that follow are shaped by factors such as reinforcement, handler responses, as well as the context, the dog’s emotional state, age, and health status, and so on.

Common pressure points include:

- distractions increased too quickly

- duration and distance raised together

- reinforcement thinned before stability

- reinforcers used are not motivating to the animal

- cues tied unintentionally to posture or environment

- elevated arousal affecting performance

Viewed this way, the diagram functions as a diagnostic tool rather than a judgement on where you are in the process.

With this in mind, the New Year presents an opportunity to rethink training, not in terms of doing more, but in terms of understanding where learning has, and has not, transferred.

Effective training is iterative. Criteria are set, outcomes observed, variables adjusted, and success protected. When behaviour weakens, the most useful question is structural: which stage of the cycle needs revisiting, and which variable changed?

If your dog’s training feels solid at home but unreliable elsewhere, or if behaviours unravel as environments become more complex, a structured review can help identify where learning has stalled and how to rebuild it in a way that supports both reliability and welfare. If you feel stuck and are looking for a more structured, evidence-led approach to training, you are welcome to get in touch: [email protected]. Alternatively, check out the Animal Behaviour & Training Council’s practitioner directory for a list of qualified trainers and behaviourists.

References

- Bouton, M.E. (2007) Learning and Behavior: A Contemporary Synthesis. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

- Braem, M.D. and Mills, D.S. (2010) ‘Factors affecting response of dogs to obedience instruction: A field and experimental study’. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 125(1–2), pp. 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2010.03.004

- Domjan, M. (2015) The Principles of Learning and Behavior. 7th edn. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

- Gergely, A., Topál, J., Dóka, A. and Miklósi, Á. (2014) ‘Dogs are able to generalise directional acoustic signals to different contexts and tasks’, Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 156, pp. 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2014.04.005

- Mills, D.S., Karagiannis, C. and Zulch, H. (2014) ‘Stress and learning in dogs: implications for welfare and behaviour modification’, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 44(3), pp. 525–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2014.01.005

Learn more about our classes

Get Hanne's book, clothing and more

Hanne has a number of publications including her book Playing With Your Dog to help owners work out the games that are best suited for their pet to play throughout his life, from puppyhood to old age, available from Amazon. Check out Hanne's range of contemporary casuals The Collection – for pet lovers made from recyclable, organic materials that are sustainably sourced.