Cancer has shaped my life in the way it has shaped so many families. I have lost people I love, including my father and my bedstemor, and over the years there have been others too, friends, colleagues, people who should have had more time than they were given. The 4th February marks World Cancer Day – which aims to rise awareness of just how many people around the UK have their lives changed by a cancer diagnosis. Yet, I think days like this are more than just building awareness; they tend to bring people back into focus – the conversations, the waiting rooms, the hope, and sometimes the helplessness.

Today feels like a moment to acknowledge the people working relentlessly toward better prevention, earlier detection, more tolerable treatments, and improved survival and quality of life. Clinicians, researchers, nurses, allied health professionals, trial participants, and families holding everything together around the edges of treatment.

And, alongside that, are the many animals already part of this landscape.

The science behind animals detecting cancer

Many people have heard that dogs can detect certain cancers through scent. This is because dogs have approximately 300 million olfactory receptors, compared with roughly 6 million in humans, and tumours can release volatile organic compounds as cellular metabolism changes. In controlled research settings, trained dogs have detected cancers such as prostate, lung, breast, and colorectal using breath, urine, or blood samples (Pirrone and Albertini, 2017; Guest et al., 2021).

Alongside academic and clinical research, organisations such as Medical Detection Dogs are helping bridge the gap between laboratory science and real-world application. Their work spans early detection research, including cancer, as well as conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and infectious diseases, often in collaboration with universities, NHS partners, and clinical research teams. Like all emerging detection approaches, this work sits within ongoing scientific scrutiny around standardisation, reproducibility, and how biological detection compares with rapidly developing laboratory diagnostics such as liquid biopsy and sensor-based technologies.

Some blinded trials examining whether dogs can detect cancer via scent have reported accuracies above 80%. However, results vary widely depending on cancer type, stage of disease, how samples are collected and stored, and how dogs are trained. Earlier work also highlighted risks of handler cueing and environmental contamination. A systematic review of canine disease detection research highlighted how much results vary between studies, often reflecting differences in training approaches, sample handling, and study design (Juge et al., 2022).

So what does this mean in practice? At present, detection dogs are best understood as demonstrating biological potential rather than offering a definitive routine clinical screening tool.

How animals support cancer research and treatment development

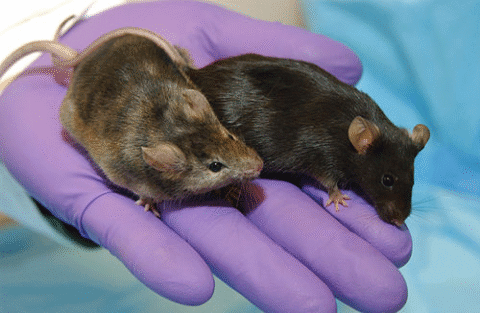

Beyond headlines, animals are deeply embedded in the development of cancer treatments. Transgenic mouse models enable researchers to study tumour behaviour, metastasis, and immune responses prior to early human trials (Day et al., 2015). Whilst zebrafish models allow direct visualisation of tumour growth and blood vessel formation in real time (Liu and Leach, 2011). These models have transformed how quickly researchers can understand cancer biology and test new treatments. Alongside that progress, it is also important to note that expectations around how research animals are used and cared for have also changed. Today, research ethics focuses more strongly on making sure the potential scientific benefit is carefully balanced against any impact on animal welfare, with ongoing wellbeing checks and a stronger focus on care and responsibility, rather than simply meeting legal rules (Mellor et al., 2020). Nevertheless, there is always room for improvement!

The role animals play in supporting people during cancer treatment

There is also growing evidence that animals can change how people experience cancer treatment. People living with companion animals often report feeling less lonely, less stressed, and better able to keep up with treatment schedules (Wells, 2009; McGhee et al., 2022).

This is something I discuss frequently with my postgraduate students when we explore human–animal relationships and psychology. In some oncology settings, therapy animals have been linked with reduced anxiety and improved emotional wellbeing during treatment. The research is still developing, and results are not always consistent, so findings need to be interpreted carefully (Holder et al., 2020; McCullough et al., 2018; Waite et al., 2018; Silva and Osório, 2018).

Animals have played a meaningful role across cancer science and care, from helping researchers understand disease processes, to supporting detection research, to improving how some people experience treatment and recovery. And for those left behind, the support we get from our pets can help us through some of the lowest moments.

While the animals supporting research, detection, and recovery rarely make headlines, their contributions have been significant in helping advance cancer science and care to where it is today.

References

- Day, C P., Merlino, G. and Van Dyke, T. (2015) Preclinical mouse cancer models: a maze of opportunities and challenges. Cell, 163(1), pp. 39–53. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.068

- Guest, C., Harris, R., Sfanos, K.S., Shrestha, E., Partin, A.W., Trock, B. et al. (2021) Feasibility of integrating canine olfaction with chemical and microbial profiling of urine to detect lethal prostate cancer. PLOS ONE, 16(2), e0245530. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245530

- Holder, T.R.N., Gruen, M.E., Roberts, D.L. et al. (2020) A systematic literature review of animal assisted interventions in oncology (Part I): methods and results. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 19. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7444110/

- Juge, A.E., Foster, M.F. and Daigle, C.L. (2022) Canine olfaction as a disease detection technology: a systematic review. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 253, 105664. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2022.105664

- Liu, S. and Leach, S.D. (2011) Zebrafish models for cancer. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, 6, pp. 71–93. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130330

- Mellor, D.J., Beausoleil, N.J., Littlewood, K.E. et al. (2020) The 2020 Five Domains Model: including human–animal interactions in assessments of animal welfare. Animals, 10(10), 1870. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/10/10/1870

- McCullough, A., Ruehrdanz, A., Jenkins, M.A. et al. (2018) Measuring the effects of an animal assisted intervention for paediatric oncology patients and their parents: a multisite randomised controlled trial. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 35(3), pp. 159–177. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29268667/

- McGhee, W.R.G., Graham Wisener, L. and Dempster, M. (2022) The role of companion animals in advanced cancer: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. BMC Palliative Care, 21, 162. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-01050-y

- Pirrone, F. and Albertini, M. (2017) Olfactory detection of cancer by trained sniffer dogs: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 19, pp. 105–117. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1558787817300539

- Silva, N.B. and Osório, F.L. (2018) Impact of an animal assisted therapy programme on physiological and psychosocial variables of paediatric oncology patients. PLOS ONE, 13(4), e0194731. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194731

- Waite, T.C., Hamilton, L. and O’Brien, W. (2018) A meta analysis of animal assisted interventions targeting pain, anxiety and distress in medical settings. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 33, pp. 49–55. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.07.006

- Wells, D.L. (2009) The effects of animals on human health and well being. Journal of Social Issues, 65(3), pp. 523–543. Available at: https://spssi.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01612.x

Learn more about our classes

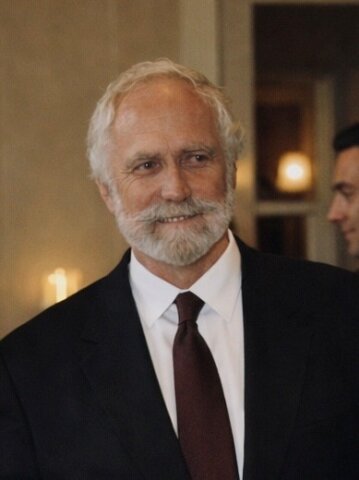

Get Hanne's book, clothing and more

Hanne has a number of publications including her book Playing With Your Dog to help owners work out the games that are best suited for their pet to play throughout his life, from puppyhood to old age, available from Amazon. Check out Hanne's range of contemporary casuals The Collection – for pet lovers made from recyclable, organic materials that are sustainably sourced.